Iryna Tofan

In mid-April 2024, a global team of Ukrainian researchers presented the new Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary in Utchecht. The glossary compiled 20 concepts from de- and post-colonial theories, featuring examples specific to the Ukrainian context. The Decolonial Glossary originated from discussions and initiatives that focus on presenting Ukrainian agency. One such initiative was a Ukrainian think tank in the Netherlands, established in response to the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The think tank aimed to address knowledge hierarchies within academia and for this, brought together Yuliia Elyas and Anastasiia Omelianiuk. Together with Iva Naidenko and Nadiia Koval, they curated the Decolonial Glossary as an international collaboration between the Netherlands and Ukraine. Though the topic of Ukrainian decolonization and the re-evaluation of power dynamic between what is now Russia and Ukraine are on the rise, the terms and the very language of such discourses remain confused. Recent conferences in Slavic Studies in the US and Europe have a profound focus on decolonial questions, yet the combination of the words “decolonization” and “Ukraine” still implies something curious and broad rather than obvious and concrete.

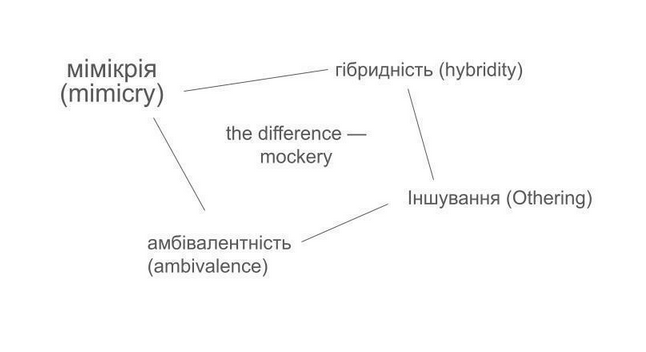

Under the umbrella of “decolonization,” one can find discussions about anything from labels in museums and how to attribute artworks properly, to questions of grammar and spelling, to the investigation of oppressive colonial practices in the times of the Russian Empire, the USSR, and the context of the current war against Ukraine. The complexity of colonial dispositions includes all of the above and many more aspects, and in order to articulate, acknowledge, and mitigate them, we need to cultivate a concise language to speak about Ukrainian decolonization, and back it up with facts. The Decolonial Glossary addresses many of the aforementioned issues in its entries. Articles are packed with information and additional resources in the form of crosslinks between entries, endnotes, and references, and hyperlinks to outside portals.

Why has it been such a challenge to articulate Ukrainian decolonial discourse? Well, there are many explanations: lack of Ukrainian representation in Western academia, lack of attention to decolonial theories in Ukrainian academia, lack of interest, and lack of understanding, are some. There is also a lack of words: written, spoken, read, and reflected on. Many of these factors are rooted in epistemic injustice; such as when the voices of Ukrainians are not considered credible to speak about Ukraine, unlike their Western or Russian counterparts. Twenty-four years ago, in her groundbreaking work on colonialism and Russian literature, Professor Ewa Thompson identified a number of reasons that allowed the vacuum around Russian imperialism to exist for such a long period. She mentioned that postcolonial writers at the time were interested in racial rather than national problems and did not apply a decolonial lens in the context of Slavic Studies and the history of the Russian Empire – USSR – Russian Federation.[1] Originally, in postcolonial theory, it was assumed that colonies were usually far from the metropolis and their conquest required overseas campaigns. Thompson highlights that the proximity of Russian colonies to ethnic Russian lands distorted the border line between them, obscuring the true nature of the relationship between the metropolis and the periphery.[2] These ideas, and the way Thomspon dissected famous Russian literary works from a decolonial perspective, were among the first articulations of the colonial essence of Russian culture and its reign throughout the centuries.

The silence about Russian colonialism was not only an external issue but also internal, in Ukrainian society and academia. In 2001, Professor David Chioni Moore noted that scholars specializing in the former Soviet-controlled lands were not considering their regions in postcolonial terms, which had been developed by scholars from other regions such as Indonesia and Gabon.[3] This echoed the ideas of Thompson, who also pointed out that Europeans who have been subjected to the colonial aggression of Russia or other empirical powers are the last to acknowledge that they were actually the targets of colonization.[4] The Ukrainian decolonization effort required acknowledgment and development within Ukraine and in the fields of Slavic and Eastern European studies worldwide.

Since the publication of Imperial Knowledge, the decolonial discourse in general, and in relation to Russian colonialism, has substantially evolved. The Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary provides a snapshot of current developments and customizes it specifically to the Ukrainian context. Importantly, it tackles the above-mentioned issue of epistemic injustice, giving space within the glossary to the voices of Ukrainian scholars at different stages of their careers and who are residing both across the globe and in Ukraine. By actively engaging with scholars from around the world, particularly in the Global South, the Decolonial Glossary further stitches together developments in decolonial studies and integrates Ukrainian elements. Together, this contributes to a new vision of possible world dynamics after colonialism and an understanding of what colonized nations collectively inherited from past political structures.

The Decolonial Glossary incorporates numerous references to modern and contemporary Ukrainian art and culture to illustrate its terms, including iconic movies like Zemlya by Dovzhenko, artists and dissidents from the 1960s, contemporary writers like Andruchovych, and a range of contemporary visual artists like Kulikovska, Ralko, Leiderman, and others. For those who are familiar with these works, it makes it easier to understand the concepts. For those who are not, it provides additional avenues for exploration and research of Ukrainian art and culture.

Beyond being just an illustration, culture can help reveal and highlight many aspects of colonial dynamics even more explicitly than economics or sociology. Literature, visual arts, theater, and other art forms directly reflect colonial struggles and provide a means to reflect on them. In a classic decolonial reading of works by authors such as Jane Austen or Leo Tolstoy, researchers point out the explicit and implicit ways in which colonial infrastructure is integrated into the lives of the characters and the narrative. This includes examining the source of wealth of prominent families, social stereotypes, and perceptions that drive character interactions, as well as the ways in which lands and cities are portrayed (i.e. as an exotic place, a place of exile, or synonym of a wasteland). Analyzing a book as a cultural product can also reveal political and economic hierarchies, such as through the number of editions published, their distribution, accessibility, translations into different languages, and circulation statistics.

Intellectuals like Tehmina Goskar, Botakoz Kyssembekova, Misho Antadze, and Maria Hlavajova have provided feedback through collaboration and a cross-review process with the authors of the entries. And according to the project curators, one of the challenges faced by the Decolonial Glossary is the emphasis on the national aspect in its title. This concern is understandable given the current rise of right-wing populism and the resurgence of nostalgia and nationalistic sentiments in Europe. However, in Ukraine’s case, the focus on the national is a direct response to the ongoing erasure of Ukrainian identity, which is rooted in our prolonged history of – not just the recent – ongoing invasion. The history of attacks on Ukrainian culture and identity from colonizers includes the suppression and discrimination of the Ukrainian language over centuries, the persecution, arrests, and murder of Ukrainian intellectuals, the displacement of people, and the physical destruction of cultural heritage sites. The list goes on. Using a term like “Soviet occupation” instead of “Soviet period” demonstrates a sensitive and accurate articulation of power dynamics between Russia and Ukraine that often go unquestioned.

The collaborative and reflective creation of the Decolonial Glossary allows for clear and precise communication of decolonial terms and concepts, like in this example of “Soviet occupation” used in Maria Vtorushina’s entry on the coloniality of gender. Contributors were not writing in isolation from one another, instead, the approach was to host workshops and seminars that brought together scholars and artists to share and develop theories. These discussions allowed the glossary to be well-equilibrated and sensitive.

One of the common fears articulated, or implicitly present throughout the glossary, is a fear that Ukrainian decolonial discourse remains in the gray zone, doubled now by the risk of physical destruction that Ukrainian society faces due to this war. In the entry borderlands, Daryna Skrynnyk-Myska put it simply: “In 2004, Poland’s eastern border became the external border of the European Union,” and Ukraine, in this scenario, is a “periphery of the periphery” of what is perceived as the Western world. Hence, Ukraine is almost excluded from the European mental map and discourse from the West, and simultaneously overwritten and overshadowed by Russian narratives and propaganda from the East. This overlap is a gray zone that is a very troubling place to be.

Ukraine was not much visible in the Western mnemonic landscape, and even after the annexation of Crimea, the Russian war in Donbas, and the full-scale invasion in February 2022, Ukrainian voices remain overshadowed by Russian voices in media, academia, and popular culture. Russian so-called liberals are often asked to comment on the situation in Ukraine, a movie about a Russian politician won an Oscar, and Forbes and The Washington Post have highlighted the challenges faced by Russian international students in the US under headlines like “Biden Officials Should Protect Russian Fulbright Scholars.” However, there are no corresponding articles addressing the difficulties experienced by Ukrainian students in the US. This disparity can be due to a lack of understanding of how detrimental such cases are to the Ukrainian struggle or internal policies of the committees, or any number of other reasons. However, the choice to give a platform to Russian voices aligns with what is known as the “coloniality of knowledge.”

As Stefania Sidorova puts it:

“[c]haracteristic features of the coloniality of knowledge are the inferiority complex of colonized communities, their intellectual and academic dependence on former colonizers, the internalization of imperial narratives, the inability to, or struggle with, going beyond the framework of the dominant discourse, the absence of direct connections with the world not mediated by the metropolis…”

The format of the Decolonial Glossary allows one to read and interact with the text in any order, yet for those unfamiliar with Ukrainian decolonial topics, the curators suggest starting with the entries by Yuliia Kravchenko and Myroslav Shkandrij, which are texts explaining Anticolonial/Postcolonial/Decolonial nuances. Another entry point for the glossary may be the text by Svitlana Biedarieva, where she discusses the shift from the Postcolonial Condition to the Decolonial Option or Gennadi Poberezny’s article on how genocide is connected to imperialism through Raphaël Lemkin’s Concept of the Soviet Genocide in Ukraine. Unfortunately, the glossary lacks a search option, which could have made interacting with the information more accessible. But for now, the user can pick one of these texts or any of the terms from the alphabetical list and begin their exploration of decolonial concepts.

The project’s curators intend to update the glossary with new terms, reflecting ongoing research and evolving discussions in the field, and are exploring funding and partnership options to do so. One of their goals is to increase the diversity of voices and perspectives represented in the glossary, including those from different regions of Ukraine and from communities of Crimean Tatars, Jews, and Roma. This diversity will lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the decolonial struggles within the Ukrainian context. Additionally, the project team seeks to explore how the Ukrainian experience and work can help various decolonial movements worldwide by connecting and sharing insights to inform and support their efforts. As the Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary expands, the goal is to develop the digital version into a physical, published book.

Colonial practices do not end with any particular historical moment. Neither declaration of independence nor war cuts off at once the colonial power constellations that have for centuries, created and solidified so many repercussions, both obvious and subconscious. Language is a powerful tool for bringing to light stories of inequality, asymmetry, and oppression, and for seeking solidarity with those affected by colonial powers.

The Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary is funded by the European Union under the House of Europe program.

________________________________________________________________

Iryna Tofan, Fulbright Fellow at New York University’s Museum Studies Program in 2022–2024. Born in Kyiv, Ukraine, she is a former Research Fellow at PinchukArtCentre and Communications Manager at the National Art Museum of Ukraine. Currently, Iryna is a Curatorial Fellow at the Ukrainian Museum in New York City.

Her research interests include Ukrainian art of the 20th and 21st centuries, digital technologies and contemporary art, war visual rhetoric, and decay and destruction in art.

[1] Ewa M. Thompson, Imperial Knowledge: Russian Literature and Colonialism, Contributions to the Study of World Literature, no. 99 (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2000), 36.

[3] David Chioni Moore, “Is the Post- in Postcolonial the Post- in Post-Soviet? Toward a Global Postcolonial Critique,” PMLA, Modern Language Association, 116, no. 1 (2001): 115.

[4] Ewa M. Thompson, Imperial Knowledge: Russian Literature and Colonialism, Contributions to the Study of World Literature, no. 99 (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2000), 40.