Siona Wilson

Only some of the girls in this show have eggs, but we have all eaten them. Eggs – soft boiled, hard boiled, poached, deviled, scrambled, over-easy, sunny side up, coddled – lovely, golden, tasty, wholesome eggs. Eggs: the socially acceptable abortion.

Boy asks girl: how do you like your eggs in the morning?

Girl answers: unfertilized!!!

There’s a girl in Texas on the run, chased by gun toting cowboys and cowgirls. This mob of Stetson-wearing vigilantes gallops after her, swinging lassos, kicking up dust, charging her down. Ready to corral. She’s a container of precious eggs. Eggs from God. Eggs that must not be broken. Fuck the girl, protect the eggs!

There’s a girl in Krakow heading for Berlin. Nauseous, she rides the Flixbus. The toilet is broken, her sickbag has split. She’s a container of precious eggs. Eggs from God. Eggs that must not be broken. Fuck the girl, protect the eggs!

Girls + Eggs is an exhibition in alliance with all these outlaw girls. Girls on the run. Girls who have run out of eggs. Girls with runny eggs. Some of the eggs have migrated. Some of the girls were once boys. Some of the girls are still boys. Boys with mutated egg sacks. Testes are overcooked ovaries. Their eggs failed, fallen, dropped off the wall, like Humpty Dumpty. Oh dear! Whoopsie daisy!

C U at Sadka! An exhibition in a house, in a garden, in the suburbs of Krakow comes to the Shenandoah Valley in the Commonwealth of Virginia (by way of Staten Island, New York).

— GIRLS + EGGS curatorial text

Girls + Eggs is a ridiculous title. Hysterical laughter is sometimes the only response when women have been rendered incapable of making decisions about their bodies and lives, when the police detain and interrogate girls after experiencing miscarriages, when doctors dare not treat dangerous ectopic pregnancies in case a politicized court decides that “risk to life” was not yet met, and underage pregnant rape victims are forced to give birth or prosecuted for seeking an abortion elsewhere. All of this, when the US still has no mandatory maternity leave, politicians prop up a for-profit healthcare system in utter chaos, Black and Hispanic women are four times more likely than white women to die in childbirth, and huge numbers of the sick are bankrupted by medical debt. So, we laughed a lot when the idea of the exhibition first came about in the early hours of the morning after a long night of fun. But our laughter was driven by rage. This was the summer of 2021. I visited Krakow as part of my first overseas travels since the lonely months of the pandemic. Agnieszka Szostek and Michael Biber, who I knew from time I spent in Berlin, moved to Krakow in 2020 (a return home for Szostek, Biber is German). They bought a rundown traditional wooden country house in the suburbs of the city (fig). It’s called Sadka. This is the name of the street, but naming the house was also a kind of christening, giving her subjectivity, identity, and a new life.

Sadka was a weekend getaway that would double as an occasional exhibition space. In August of 2021, a month or so before the first exhibition in the house (titled, PPS: it’s a progressive fantasy {…}), the upstairs bedrooms were finished with new pine panels and downstairs was only lightly renovated with the torn and graffitied old-fashioned wallpaper remaining as a record of generations past. One room with wild floral walls has the spraypainted letters “TV” written in the corner like the notes of a delinquent interior decorator. At this time, Sadka had electric lighting but no functioning plumbing, so we peed in the garden and decamped to the city apartment the next day.

Before this visit, I was only vaguely aware of the mass demonstrations in numerous Polish cities protesting the new (old world) laws from 2020 prohibiting abortion in almost every case. The Human Rights Watch report on the state and church directed witch hunts against Polish women were published in 2023, but anecdotal accounts circulated on social media.[1] In Berlin, there was also some talk about this since Polish women were traveling across the border to access German health care. It seemed like time was moving in reverse. Soon after, the first rumors that the US supreme court might overturn the federal abortion law, so-called “Roe versus Wade,” were reported. But the return to pre-feminist values was already well established in the US. I made a drawing, a curatorial meditation, that we used to advertise the first version of Girls + Eggs (fig.). Laughing hysterically, the middle finger of a woman’s hand bursts out of a boiled egg, as a feminist “fuck you” to the ridiculous logic of these dark times.

Despite the election of Trump, most Poles I spoke to saw the US as the home of progressive politics. Many families had relatives who had migrated to the US, often during communist times. For them, it was a place where the repressions of the old world (the Catholic church and Communist party) held no sway, or so they thought. Perhaps this was once partly true, but a new nasty conservatism is running rampant. We’re living in a new old world, cynically celebrating its own criminal hypocrisy.

Girls + Eggs, the juxtaposition of ideas and the bringing together of works, captures our hysterical rage. I was an economy class travelling curator with an exhibition in a suitcase. Literally, the works from the US were packed into my luggage. Although some things were printed on site and others were sent in the mail, the first two iterations of Girls + Eggs involved a lot of heavy bags. Hospitality was also part of the process. The labor of curating this show, like the ideas explored in the artists’ works, was embedded in the practicalities of living, caring, and being together. In doing so, we expressed solidarity across borders of nation, region, gender, sex, sexuality, and age.

Women, men, transgender, non-binary, queer, lesbian, cis-gender, mothers, perverts, fathers, child-free, dog lovers, and feminists, Girls + Eggs stages a world of individuals, characters, thoughts, and fragments from those repressed by and resisting the return to old world patriarchal norms. The works, artists, and exhibition venues contribute to the affective landscape of the project. Sadka, the birth venue, first old-fashioned mother for our Girls + Eggs, functioned almost like another artist. She provided the anchor to place, land, domesticity, religion, and tradition. I was a curator in residence for the duration of the exhibition in June 2022. I slept in a bedroom upstairs and offered visitors tea (beer or vodka) when they came over to see the show. Like the elderly, conservative population that supported the Polish return to patriarchal values, Sadka was our grandmother muse.

When Girls + Eggs came to Staten Island, I saw this as a geographical parallel to Poland. Staten Island is to New York City as Poland is to Europe: they each belong to a larger geopolitical body, yet they are geographically, socially, and psychically peripheral. Both are less accepting of difference, more politically conservative, and officially supportive of the rollback on women’s right to choose. Each place also includes powerful voices of opposition, inclusion, and advocacy. Traveling south to Virginia, a historic region in the (old) new world, is—perhaps desperately—a kind of hopeful parallel for future change. Despite the shared conservativism, Poland has since voted out the political right and voters in Virginia refused to change the abortion laws in elections in 2023. But there’s still plenty for feminists to laugh about, hysterically.

I approached the curation of this exhibition affectively. Reproductive justice, the right to choose, to have sovereignty over our bodies, is embedded in a much broader political, cultural, and emotional landscape of sexual citizenship. Girls + Eggs animates this broader arena of feeling and living. There are only a few works in this exhibition that directly reference the issue of reproductive justice and the symbol of the egg. The 80-year-old LA-based transgender artist, Pippa Garner, is one example. The slogan tee-shirts presented on her aging body read, “If you knock me up, I’ll knock you down,” and “these are my remains.” Her photographs show performances from everyday life, from life lived as embodied performativity, laughing hysterically at the cis-gender ideals of heterosexual reproduction and taboos about a body aging. Peter Kunt, Piotr Dłużniewski, and Martyna Borowiecka each made egg-themed works in response to the acidic tone of camp carnivalesque expressed in my curatorial statement (fig.). The second version of the show, at the Art Gallery of the College of Staten Island, included Beatrix Reinhardt’s Untitled (2022) (fig), that used eggshells as miniature plant pots to grow weeds she had propagated from sidewalk cracks and local parks. Egg cartons and an ostrich egg also appear in photographs featuring African models. While these works, made during a residency in South Africa, were about being out of place not reproductive justice, Reinhardt was happy to plant her ideas amidst the girls in our show.

Other works approach the topic indirectly. Biber’s Flags on a Line, installed on a washing line in the garden of Sadka, evoke domestic gendered labor, protest, and confused nationalism, but the fabric, offcuts of soccer jerseys, is archetypically masculine, macho even. The tradition of geometric abstraction here occupies the site and materials of other social spaces (fig). At the same time, this work connects with Sonia Delaunay and Sophie Taeuber Arp’s early abstract quilts, evoking the repressed feminine within the history of modernist art.

Maria Kniaginin-Ciszewska’s large-scale erotic photographs of herself and her female lover present tableau images of the kinky queer couple as part of Polish everyday life. Against the traditional walls of Sadka, these images felt even more provocative (fig). Home is as much a site of repression and violence as it is a place of comfort and safety. Monika Drożyńska’s embroidery works animate and parody the contradictions within traditional domesticity. Evoking the widely held anti-immigrant feeling in Poland, notions of home, of belonging are cut through with the inverse. Her video animation, American Dream is Dream, references the racist treatment of Poles in the US, along with other “white” ethnic groups, suggesting a cycle of victim to oppressor. Madeline Kuzak’s intricate pencil drawing, Bowers of Bliss, offers a shard of collective female cruelty, a fragment of a dark narrative in which women violently persecute other women. The politics of reproductive justice includes women on both sides of the issue.

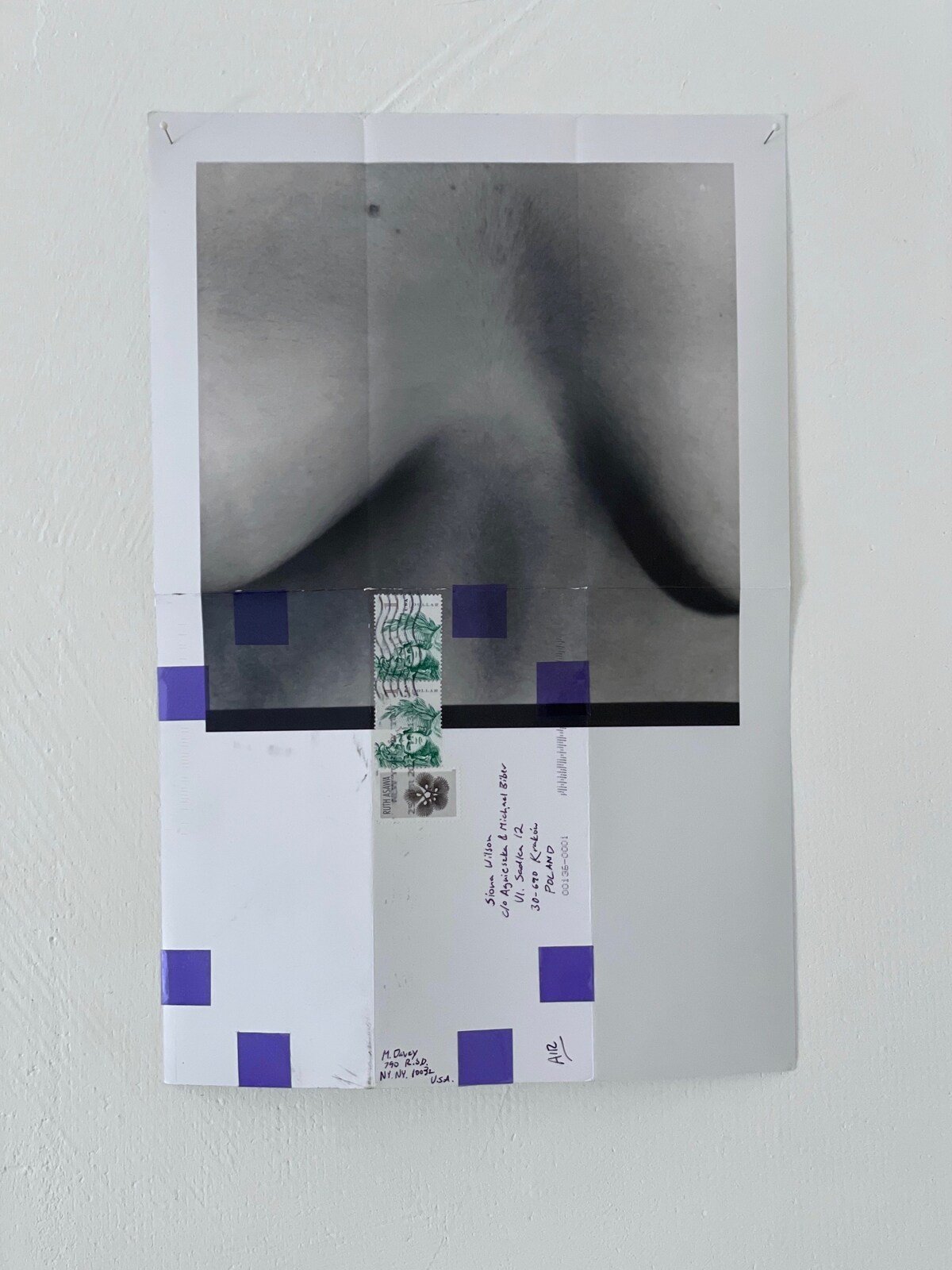

Kuzak and Kniaginin-Ciszewska are early career artists, but their work sits amongst contributions from established feminist figures. Moyra Davey printed some old negatives dating from her art school years in the 1980s. As another echo of domestic norms, these three images arrived in the mail at Sadka folded into self-made envelopes (fig). As with other photographic works by Davey, the postage and address labels are a visible part of the surface of the images when presented unfolded and simply pinned to the gallery wall (fig). The modesty materiality and quiet imagery contrasts with the “stilt coupled with bloat,” associated with the staged scenes and high production values of museum-ready large-scale tableau form photography.[2] Mira Schor, an original member of Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s Feminist Art Program at CalArts in Los Angeles and participant in its landmark exhibition, Womanhouse (1972), contributed facsimiles of her Instagram series New York Times Intervention. Schor’s habit of reading the morning paper became a studio practice of enraged feminist graffiti. Begun after the election of Trump, these crude edits scrawled directly on to the physical newspaper were made in response to the anodyne commentary of the New York Times. These works operate on the walls of the exhibition space as something like the screaming signage pasted in the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920 (fig).

Szosek’s Untitled (War doesn’t mean the End of Fashion. Sanctions on Russia are the Inspiration), a latex A-line skirt imprinted with a collage of commercial imagery from communist era Poland and present-day luxury stores, was made in response to the war in Ukraine. Another echo of the Dada fair (the ur-form for avant-garde protest exhibitions), in the use of a display mannikin, “the bitch,” as she was fondly known, became an uncanny resident of Sadka. Both object and space combine the old world and new, this, and Szostek’s other latex works are like diseased skin with a hint of the fetishistic. Kat Chamberlin’s chiffon prints, framed loosely with clean, tight vinyl echo with Szostek’s works. Her cryptic micro poems, Sex and Death and Gash on a Lash, operate like a cypher or an unknown alphabet, since they are not easily readable.

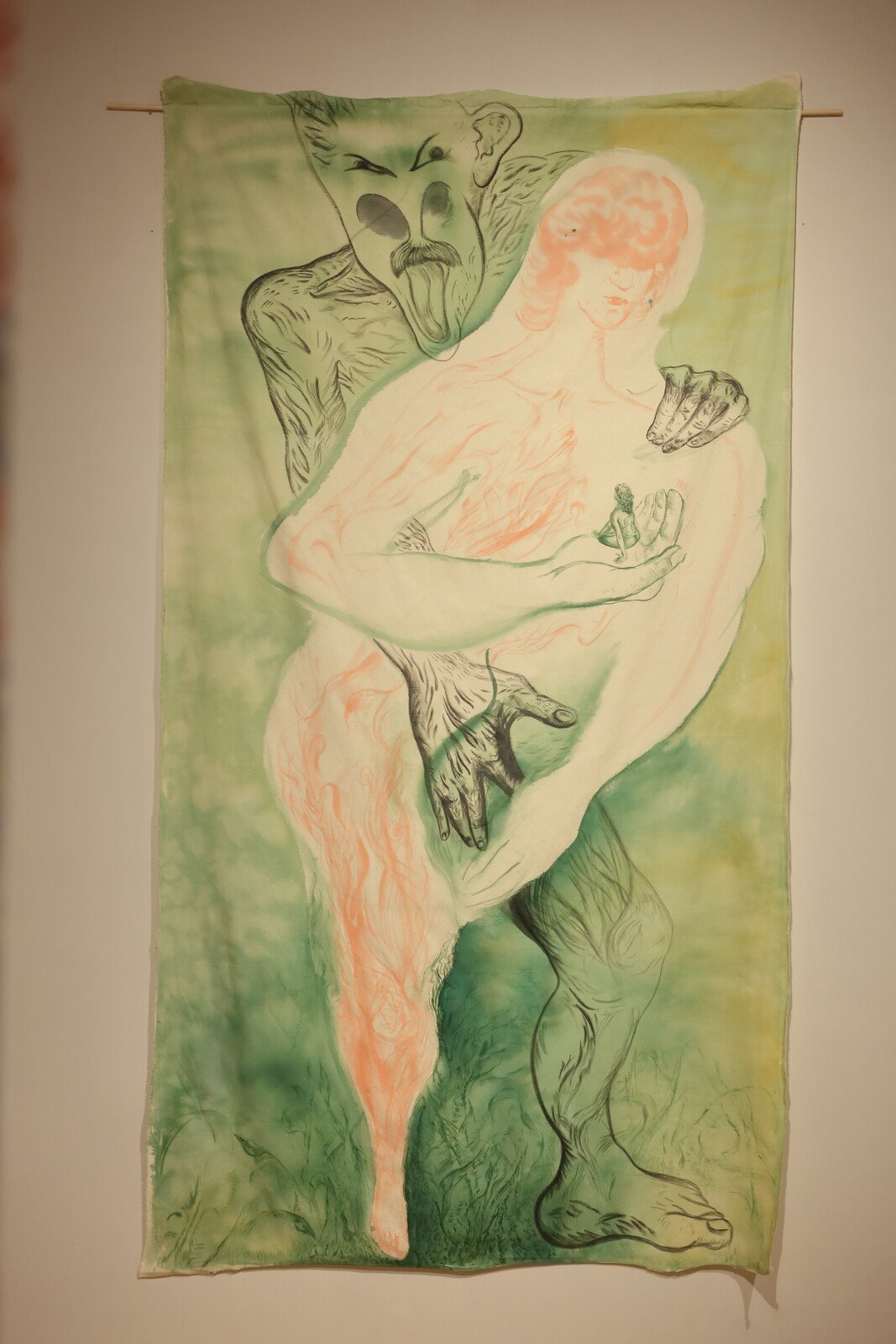

As with Chamberlin and Szostek, materials—in this case, found materials—are eloquent with condensed references in the sculpture of Danni O’Brien. Together with Maja Krysiak, O’Brien is a new addition to the Duke Hall Gallery version of Girls + Eggs. A graduate of the BFA program at JMU, O’Brien mobilizes a sinister eroticism that combines the gynecologist’s office with the used bookstore and the kitchen pantry. While O’Brien’s sculptures are fragile and precarious in their congregated arrangements, Krysiak’s free-hanging cloth painting draws on the representational language of violent gendered mythology. Her depiction of the diminutive female held in the palm of a monstrous giant is an old-world reference that seems ever new.

From the transgressive excitement of Kniaginin-Ciszewska and Dłużniewski’s erotic works to the blazing fury of Schor’s protest scrawls, the affective mood shifts down gear with other more contemplative works. Oskar Korsár’s intense series of portrait drawings of imaginary figures—female and gender queer—seem lost in interior thought. Interspersed amongst the other works, these pensive characters operate as avatars for the many pregnant girls—past, present, and future—nauseous, riding the flixbus to Berlin, where Korsár lives. They might also evoke the somber disquiet of the desperate girls travelling across the US to find an abortion providing state.

The mythic is domesticated in Arobal’s Self Portrait Pregnant and Magda Buczek’s Castor, Pollux, Cervix. Waving the soccer scarf, for Castor and Pollux, children of rape, born from an egg, no cervix in site, turns the disavowal of the feminine into the collective chant. Arobal’s tender image of the reproductive body as queer exists alongside works that assert the suppression of the maternal (a longstanding theme in western art). Greek mythology, with narratives of rape and violence, also expresses the masculine desire for autogenesis.

The affective curating at work in Girls + Eggs positions motherhood within a complex field of meaning and feeling. The strong feelings elicited by the backward shift in political culture are the kind that propel action, protest, and strong expressive assertions. But the issue of legal prohibition extends into other affective territories and connects to other forms of repression of sexual citizenship. Whose bodies count? Which bodies are permitted to exist and where? The picture we used for the final presentation of Girls + Eggs, Kat Chamberlin’s Image to Stand on, suggests the denigration that underpins a politics of forced maternity. The menopausal curator stands on the carved aluminum depiction of the word “mother” rendered in a font that evokes punk. Yet mothers, the artist as mother, all the failed mothers, the refusal to mother, motherhood as part of the cultural sourcebook of artistic expression, the mother is still under erasure. She is usually limited to a very narrow affective range that oscillates between sentimentality and embarrassment. The mother is either elevated and emptied out of complexity or denigrated as beneath consideration.

She is a fart in the chapel of art.

[1] “Poland: Abortion Witch Hunt Targets Women, Doctors” Human Rights Watch, September 14, 2023. Accessed, January 15, 2024: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/09/14/poland-abortion-witch-hunt-targets-women-doctors#:~:text=Cases%20that%20Human%20Rights%20Watch,eliminated%20legal%20abortion%20in%20Poland.

[2] Moyra Davey, “Notes on Photography & Accident.” Long Life Cool White: Photographs and Essays by Moyra Davey (2008), 2.

Artist(s): Agnieszka Szostek, Mira Schor, Beatrix Reinhardt, Danni O’Brien, Madeline Kuzak, Peter Kunt, Maja Krysiak, Oskar Korsár, Bartek Arobal Kociemba, Maria Kniaginin-Ciszewska, Jakub Hošek, Pippa Garner, Monika Drożyńska, Piotr Dluzniewski, Moyra Davey, Kat Chamberlin, Magda Buczek, Martyna Borowiecka, Michael Biber, Kozlov

Exhibition Title: GIRLS + EGGS

Link: https://www.jmu.edu/dukehallgallery/exhibitions-23-24/girls-plus-eggs.shtml

Venue, Place (Country/Location)+Dates:

C U AT SADKA, Krakow, Poland

10–17.06.2022;

The Art Gallery of the College of Staten Island, New York

10.11–06.12.2022;

Duke Hall Gallery of Fine Arts, James Madison University, Virginia

30.01–08.03.2024.

Curated by: Siona Wilson